Find a Financial Advisor in Columbia

Financial Planning & Investment Management for Every Season of Life

Our financial and investment advisors in Columbia, MD serve clients in Baltimore, Washington, DC, Central Maryland and throughout the country. We want to be there to guide you through life’s transitions – retirement, career changes, and marriage transitions.

We’re active members of the Baltimore-Washington metropolitan area community. In Columbia, MD, a city originally designed for “joyous living,” we help design customized tax-efficient financial plans and investment management for clients in every stage of life, based on their unique goals.

Our fiduciary advisors are adept at serving the needs of our Columbia, MD community. Stop by our office and enjoy our beautiful view of Lake Kittamaqundi on the Columbia Lakefront. You will find that our advisors are approachable, knowledgeable, and ready to provide personalized advice that is friendly, clear, concise, and complete.

OUR FOCUS IS TO CONNECT YOUR MONEY WITH YOUR life.

Financial Planning

Investment Management

Retirement Planning

Resources

8 Blunders to Avoid in Retirement

For many retirees, this momentous event creates apprehension and fear. But, it doesn’t have to be that way. With the proper planning strategy, you can move toward your future with certainty and excitement.

3 Methods to Help Avoid Running Out of Money

What’s the No. 1 fear in retirement? Running out of money. Get our step-by-step guide to help ensure your assets last a lifetime.

7 Tips to Help Successfully Transfer Wealth to Your Kids

Seventy percent of family wealth is lost by the end of the second generation and 90 percent by the end of the third. Get our step-by-step guide to help you successfully pass your wealth to the next generation.

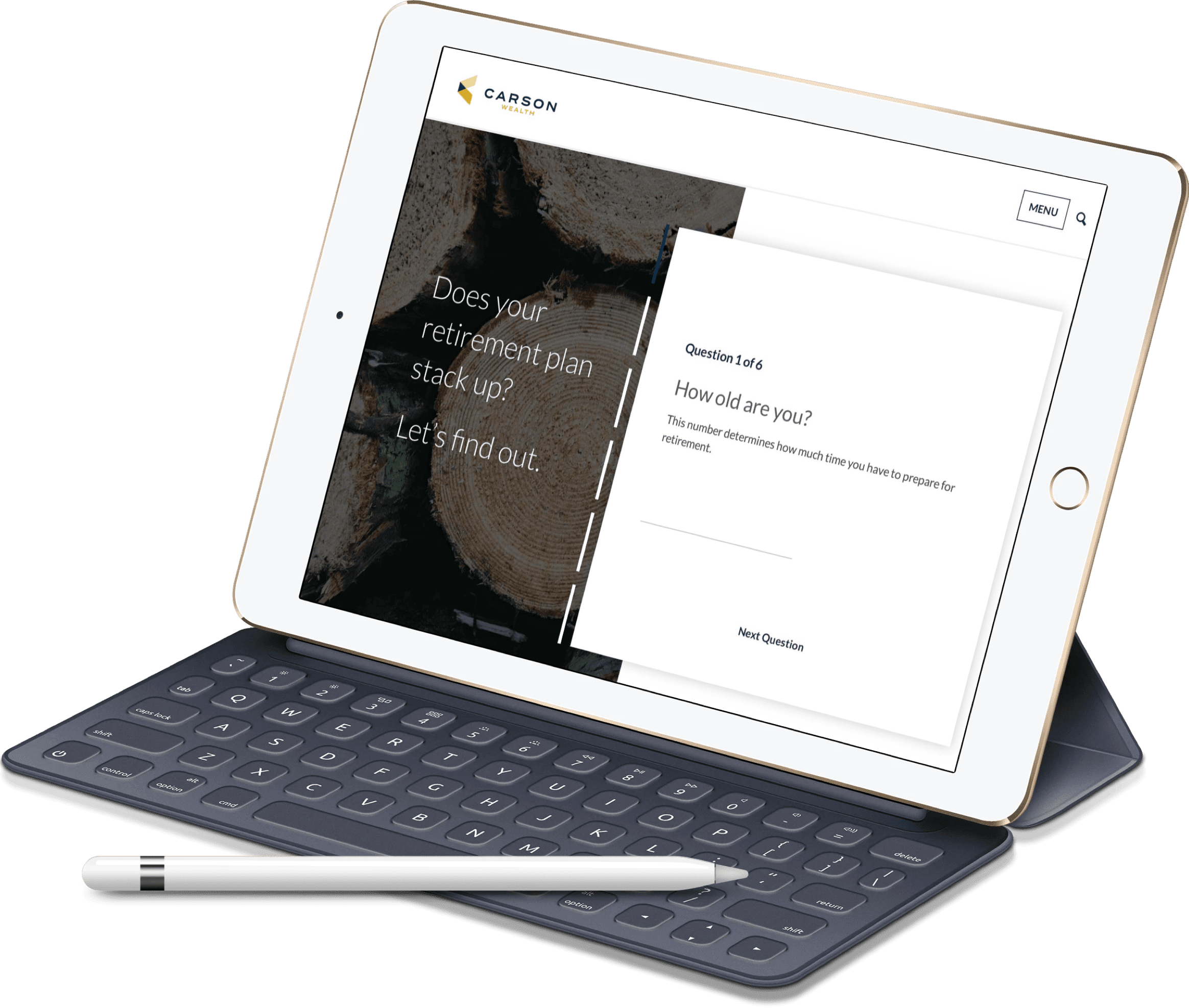

HOW FAR ARE YOU

From Being Ready for Retirement?

Our Advisors

Primary Service Areas:

Baltimore, Columbia, Savage, Jessup, Elkridge, Clarksville, Ellicott City and more.